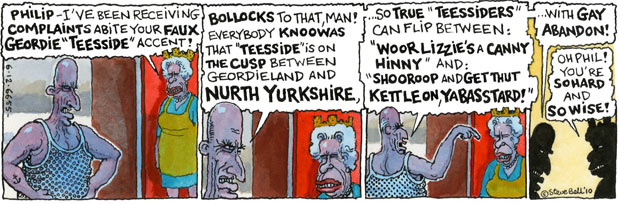

(Click cartoon to enlarge.)

(Click cartoon to enlarge.)“Knoowas” for ‘knows’ represents the northern east-coast opening diphthong for GOAT, ʊɔ.

“Shooroop” for ‘shut up’ represents ʃʊrʊp. This has not only the familiar northern use of ʊ in STRUT words, but also the outcome of what I call the “t-to-r rule” (AofE p. 370).

I don’t think there has been much discussion of this process in the literature. My impression is that it extends from somewhere in the English midlands (Coventry or thereabouts) up to the Scottish border and that it is always stigmatized. Unlike American t-voicing (tapping, ‘flapping’), it operates only after short vowels.

I don’t think there has been much discussion of this process in the literature. My impression is that it extends from somewhere in the English midlands (Coventry or thereabouts) up to the Scottish border and that it is always stigmatized. Unlike American t-voicing (tapping, ‘flapping’), it operates only after short vowels.It features in Cilla Black’s catchphrase a lorra lorra laffs ‘a lot of laughs’.

Hello John,

ReplyDeleteI often see the terms 'tapping' and 'flapping' used interchangeably, which suggests they mean the same way of articulation -- but if they do, why are they referred to by two different names? If, however, they are not the same, why are these terms used interchangeably?

Because not everyone follows Ladefoged in distinguishing between flap (ballistic movement in one direction, striking a passive articulator on the way past) and tap (back-and-forth gesture bouncing back off a passive articulator). For those who distinguish the two terms, as I do, the AmE voiced t is a tap in most positions, not a flap. But the important thing is surely its voicing, not its precise manner of articulation.

ReplyDeleteI really don't understand the difference in voicing. How do I go about making it voiceless or voiced?

DeleteThe Northern English t-to-r seems to operate in pretty much the same set of words in which some other British English speakers have lexically restricted tapping. I don't have genuine t-to-r, but I do have a tap as a possibility in almost all the situations where it occurs, and almost nowhere else. (This potentially leads to minimal pairs between [ɾ] and [t], such as "matter", verb and noun, and "pretty", adverb and adjective, but it isn't as simple as this: [t] is always a possibility in careful speech, and there's also the possibility of a Scouse-style slit (non-sibilant) fricative in both types of word.)

ReplyDeleteWhy the spelling "Nurth Yorkshire"? Do they think Teesiders use the ɵ: in NORTH? I imagine that they use ɔ: or the broader variant ɒ:, as is the case in other areas that use ɵ: in GOAT.

ReplyDeleteAlso why "thut"? Is the u supposed to represent /a/? If so, why didn't he spell bastard as "bustard"? I think that only Londoners would associate the letter u with the sound /a/. Maybe it's supposed to be a schwa.

I think the t-to-r replacement is declining as t-glottaling spreads.

^ Meant to write:

ReplyDeleteWhy the spelling "Nurth Yurkshire"?

You know, if you listen to the Queen (plenty of clips on YouTube), she does not pronounce "about" as abite. Where did this idea ever come from? I've even watched the old videos and she didn't do it then either.

ReplyDeleteI've always thought a tap is what is used in e.g. Spanish or Italian, but if a tap is what is used in AmE as the usual realization of a voiced /t/, then what sound does the 'r' in Spanish or Italian 'caro' denote?

ReplyDeleteTeardrop: The same thing. The bilingual daughter of a friend of mine bears the euphonious Spanish name of Taira, but her "American" (anglophone) friends think of her name as "Tide-a".

ReplyDeleteJohn Cowan: No, they are certainly not the same sounds, even I can hear the difference between them, but they are quite similar, indeed, which explains why her American friends associate the 'r' in her name with their own voiced /t/, because that is the closest English sound.

ReplyDelete@ John Wells: Excuse me, I'm an amateur. What does the _# V in your rule 194 in the image mean?

ReplyDeleteI noticed that the t at the end of about in "What about him?" doesn't become an r. You are right on this. It's the sort of thing I've never noticed but this t would definitely not become an r in the north. I presume your rule explains why not. I'd be interested to know.

@teardrop, not 100% the same sounds (though they can be, for some speakers in some contexts), but close enough to merit the same symbol.

ReplyDelete@ John Cowan: I'm not sure if those are the same sounds or not. When I listen to languages that have an alveolar tap as their rhotic (or one of their rhotics), my American ears never here this sound as a "t" or "d". If they were the same sound, you would expect this to happen, wouldn't you?

ReplyDelete@ John Cowan: Although I will admit when I hear an alveolar trill done right by a native Spanish speaker, it does sound like it begins with a /d/ to me. Also when I've heard accents of England that sometimes realize intervocalic /r/ as [ɾ], I have been confused. I heard an Englishman refer to someone else as what sounded to me like "an audible man". It took me weeks to realize he was saying "an 'orrible man" (he had H Dropping and intervocalic /r/ as [ɾ]). This kind of thing has happened to me more than once. I'm sorry this is OT, but the reason I bring it up is because I think the intervocalic /r/ in these accents is the same as the Spanish one in pero and this is a misunderstanding I've had that might indicate that the sound in Spanish caro (and merry in some Eng. accents) is the same as the one in my (Am. Eng.) pretty. I'm not sure though.

ReplyDelete@ anon at 16:42 -

ReplyDelete'#' = morpheme boundary, word boundary.

There can be no t-to-r in about because aʊ is not a short vowel. (Diphthongs count as long vowels.)

/r/ for /t/ occurs in popular Dublin speech in less restricted environments. Gay Byrne had "excira and delira" ("excited and delighted") as a catchphrase. Admittedly, that was stage-plebeian; his usual voice was very elocuted.

ReplyDeletePeople often seem unable to tell whether I'm saying "what is" or "where is" with greater than chance frequency.

ReplyDeleteI'm delighted you mentioned this. The same process occurs in 'Local' Dublin accents (as Raymond Hickey terms them), and I think it can extend to long vowels too.

ReplyDeleteThere is a stock nickname for a berserker-style party animal - a 'madourravit' (mad out of it).

There is also a funny song called 'Gerrup outta dat', which has a large number of examples of the usage

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EySGdiO-iBg

(note that the 'local' accent is genuine, but the posh southside accent is heavily exaggerated)

I should also add that i've never been able to work out when this linking R occurs, and when there is a t-flap. Even the spelling of the name of the song indicates this variation. In the song, I think the 'outta' part seems to vary between R and a flap

ReplyDeleteIn Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (the book), Ron, who I thought was supposed to be a southerner, says "gerroff" for "get off".

ReplyDelete@ John Wells: thank you very much for the explanation!

ReplyDelete@ Tonio Green: Yes, I am sure the feature is present in the south of England too. 'Gerraway' would be another example.

ReplyDeleteBut isn't this a feature found more widely still - e.g. in Low German?

I think, when southerners say things like 'gerroff', it's in conscious or unconscious imitation of northerners.

ReplyDeleteประเด็นเด็ด ดราม่าข่าวกีฬา พร้อมข่าวปันเทิง อันโตนิโอ นักเตะยอดเยี่ยม

ReplyDeleteI will be looking forward to your next post. Thank you

ReplyDeleteอัพเดทข่าวหวยตามกระแส >>> ทำนายฝัน ฝันเห็นจระเข้ คำทำนายฝัน พร้อม เลขมงคล